Background

The Eurasian red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) a native species to the UK that could be found in both deciduous and coniferous forests has been undergoing catastrophic declines since the 1930’s with their ranges being restricted to mostly coniferous forests. One of the main causes of the declines has been attributed to a non-native species of squirrel, the eastern grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). The grey squirrel has been introduced in various places throughout the UK since the late 19th Century by the Victorians with the earliest known introduction being in 1876. Current population estimates are around 160,000 individuals with 75% of these being found in Scotland with the remainder being found in habitat patches throughout the UK.

Due to the declines of the much loved red squirrel being very publicly blamed on the grey squirrel it comes as no surprise to me that a UK polling opinion had a 69% yes response, when asked if the public wanted the grey squirrel populations to be managed in some way.

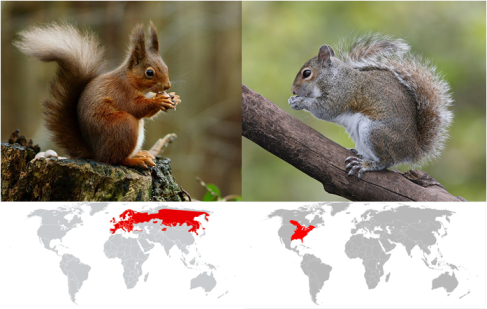

Pictured left: Eurasian red squirrel. Pictured right: Eastern grey squirrel

Pictured bottom left: Natural range of the Eurasian red squirrel

Pictured bottom right: Natural range of eastern grey squirrel (not including introduced populations)

The red squirrel is generally a lot smaller than the grey squirrel and is not as adaptable as the greys. The public’s understanding of the threat of the grey squirrel is quite limited to either thinking the greys are outright predating on the reds in some sort of squirrel race riot to a vague understanding of habitat destruction and disease. This is becoming better however, due to heavy media coverage.

How are the greys displacing the reds?

A general trend observed in areas where the two species coexist is, that while the reds are still reproducing at the same rate, the younger reds have difficulties surviving, causing the populations to ‘fizzle out’ as they are outcompeted by the more efficient greys.

This can’t be said for spruce forests however, where the greys advantage over the reds is negated due to greys having a higher daily metabolic rate, which isn’t able to be met due to the food source gained from this type of habitat. This doesn’t mean that greys haven’t attempted to occupy these habitats however.

SQPV

Other than out-competing the reds, the greys bring another threat to the local populations. Greys are known as the main vector for the squirrelpox virus (SQPV). While the virus doesn’t seem to affect the greys, the reds are highly susceptible to it. The contraction of SPQV normally results in fatalities of the majority of reds within three weeks. This allows the greys to dominate the resources due to higher numbers and displace the red population rapidly. The virus presents itself in reds with rashes, skin lesions, general poor condition and lethargy. The skin lesions also leave the squirrel open to attack from other environmental bacterial infections. It is possible to cure the virus if caught early but this remains merely a ‘clutching at straws’ type of situation.

Scotland’s Squirrels

Populations of squirrels in Scotland do not have SQPV. Although this seems like good news there is a high risk of it being introduced to these squirrels as infection positive populations do exist in southern Scotland and on the borders with England.

The Isle of Anglesey

Positive results in the control of SPQV and the greys as a whole has come from a project being ran on the Isle of Anglesey in North Wales. This island is 720 km2 with a woodland coverage of 5%, a figure well below the national average. In 1998 individuals were trapped to try and estimate numbers. A tiny sample of 40 red squirrels was surveyed with the greys being much more dominant with 3-4000 being found. The overall aim of this project is to totally eradicate grey squirrels from the island with the help of government agencies and landowners. In 1993 access was granted into Newborough Forest. Over the recent years effort per unit catch has increased dramatically leading to the assumption that the greys are in decline on the island.

One of the reasons for this success other than the extensive trapping and killing of greys on Anglesey can be owed to the restricted access of the island with only two bridges making it possible for populations from the island and Bangor to mix. This has led to a decline in SPQV antibodies from 50-80% in 1998, to 0% today, meaning the Anglesey greys and reds are clean.

Can Anglesey’s success be transferred to the rest of the UK?

Although we call Anglesey an island it is actually a peninsula and therefore there is still the possibility of greys migrating there. In 1960, many greys got onto the island and greys have been found in Treborth not far from the main bridge.

This means the reds are also able to migrate into Bangor, contract the virus and then bring it back to Anglesey. Squirrels are also able to swim through the Menai Straits.

Summary

While it would seem the red squirrel had no hope of combatting the factors causing it to decline positive results have come from the project on Anglesey. Even if this project couldn’t serve as a blueprint, due it being on a peninsula, lessons can be learnt from it. The importance of these declines should be considered within the EU and its member states. This could lead to an increase in funding for more research to develop new grey squirrel control methods and promote best practice.

That said it is legal for any member of the public to trap and kill grey squirrels. Whether you would like to do that or not is your choice, but if you want to help conserve a charismatic, native species now is the time to do it (TO ARMS!!!!).